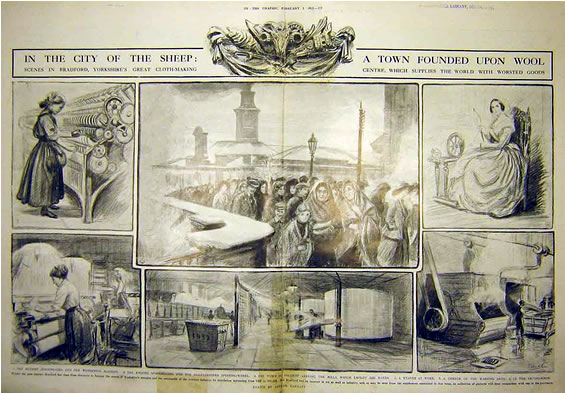

Newspaper caption: In the city of sheep, a town founded upon wool. Scenes in Bradford, Yorkshire's great cloth-making centre, which supplies the world with worsted goods. Date unknown.

In the November 27, 1852 edition of his twopenny weekly magazine Household Words, Charles Dickens gives this lively fictionalized account of Sir Titus Salt’s innovative manufacturing of alpaca fiber. I hope that you will find it as entertaining and enlightening as I have.

The Great Yorksire Llama

SIXTEEN years ago—that is to say, in the

year 1836—a huge pile of dirty-looking sacks,

filled with some fibrous material which bore

a strong resemblance to superannuated horse-

hair, or frowsy elongated wool, or anything

else unpleasant and unattractive, were landed

at Liverpool. When those queer-looking

bales had first arrived, or by what vessel

brought, or for what purpose intended, the

very oldest warehouseman in the Liverpool

Docks couldn’t say. There had been once a

rumour, a mere warehouseman’s whisper,

that the bales had been shipped from South

America on spec., and consigned to the agency

of C. W. and F. Foozle and Co. But even

this seemed to have been forgotten; and it

was agreed on all hands that the three

hundred and odd sacks of nondescript hair-

wool were a perfect nuisance. The rats

appeared to be the only parties who at all

approved of the importation, and to them it

was the very finest investment for capital

that had been known in Liverpool since their

first ancestors had migrated thither.

Well, those bales seemed likely to rot, or

fall to dust, or be bitten up for the particular

use of the female rats. Brokers wouldn’t so

much as look at them. Merchants could have

nothing to say to them. Dealers couldn’t

make them out. Manufacturers shook their

heads at the bare mention of them. While

the agents C. W. and F. Foozle and Co. felt

quite savage at the sight of the Invoice and

Bill of Lading, and once spoke to their head-

clerk about shipping them out to South

America again.

One day—we won’t care what day it was,

or even what week, or month, though things

of far less national importance have been

chronicled to the very half minute—one day,

a plain business-looking young man, with an

intelligent face and a quiet, reserved manner,

was walking alone through those same

warehouses at Liverpool, when his eye fell upon

some of the superannuated horse-hair projecting

from one of the ugly dirty bales; some

lady rat, more delicate than her neighbours,

had found it rather coarser than usual, and

had persuaded her lord and master to eject

the portion from her resting-place. Our

friend took it up, looked at it, felt it, smelt it,

rubbed it, pulled it about; in fact, he did all

but taste it, and he would have done that

if it had suited his purpose, for he was

“Yorkshire.” Having held it up to the light,

and held it away from the light, and held it

in all sorts of positions, and done all sorts of

cruelties to it, as though it had been his most

deadly enemy and he was feeling quite

vindictive; he placed a handful or two in his

pocket and walked calmly away, evidently

intending to put the stuff to some excruciating

private tortures at home.

What particular experiments he tried with

this fibrous substance, I am not exactly in

a position to relate, nor does it much signify;

but the sequel was, that the same quiet

business-looking man was seen to enter the office

of C. W. and F. Foozle and Co., and ask for

the head of the firm. When he asked that

portion of the house if he would accept of

eightpence per pound for the entire contents

of the three hundred and odd frowsy, dusty

bags of nondescript wool, the authority

interrogated felt so confounded, that he could

not have told if he were the head or the tail

of the firm. At first he fancied our friend

had come for the express purpose of quizzing

him; then that he was an escaped lunatic,

and thought seriously of calling for the police;

but eventually it ended in his making over to

him the bill of lading for the goods in

consideration of the price offered.

It was quite an event in the little dark

office of C. W. and F. Foozle and Co., which

had its supply of light (of a very inferior

quality) from the grim old church-yard.

All the establishment stole a peep at the

buyer of the “South American stuff.” The

chief clerk had the curiosity to speak to him

and hear him reply. The cashier touched his

coat-tails; the book-keeper, a thin man in

spectacles, examined his hat and gloves; the

porter openly grinned at him. When the

quiet purchaser had departed, C. W. and F.

Foozle and Co. shut themselves up, and gave

all their clerks a holiday.

But if the sellers had cause for rejoicing,

not less so had the buyer. Reader, those

three hundred and odd bales of queer-looking

South American stuff contained “Alpaca

Wool,” at that date entirely unknown to

manufacturers, and which it would still have

been but for the fortunate enterprise of one

intelligent, courageous man. That bold

manufacturer was Mr. Titus Salt, in those days a

mere beginner, with a very few thousands to

aid him in his upward career, but at present

one of the wealthiest amongst the wealthy

men of Bradford in Yorkshire. His fortune

has been altogether built up by the aid of this

same “Alpaca,” to the manufacture of which

he has for the last dozen years devoted the

whole of his time and energies.

Alpaca is the long hair-like wool, from

an animal something between a camel and a

sheep, found in vast numbers in Peru. It is

of the Llama tribe, and thrives only upon the

elevated table-lands of the interior of South

America, where it roams at full liberty, being

gregarious, but is never kept in flocks of any

number. They have been tried on the low

lands, nearer the sea-coast of their own

country, but, either from the excessive heat

or the extreme moisture of those positions,

always without success. The existence of the

wool, as also of fabrics made from it, has long

been known. Pizarro is said to have brought

portions of the raw and woven articles to

Spain on his return from his American

conquests. Attempts have, on more than one

occasion, been made to naturalize the Llama

in this country, but as yet unsuccessfully.

The late Earl of Derby possessed a few, and

these are at present in the hands of Mr. Salt,

and giving promise of multiplying.

The first sample of this hair arrived in

England in a very imperfect condition. It

now reaches us very clear and lustrous, and

is known by its extreme brightness and softness.

In colour it varies, being black, brown,

grey, and white, and of several shades of

each of these. As may be imagined, many

trials of this new fibre had to be made, and

many modifications of the existing woollen

machinery to be undertaken, before the article

could be successfully and profitably worked

up. Mechanical ingenuity has, however, overcome

every obstacle; and in the present day

we may see very many beautiful and economical

fibres produced not only with this, but

by blending it in its manufacture with cotton,

linen, wool, and even silk.

At first, none but very plain and rather

coarse goods were produced from Alpaca, and

these were, consequently, not in general

favour, although their extreme lightness has

always rendered them most agreeable for

warm weather wear. With time and patience

many great improvements have been introduced;

and now, not only are Alpaca goods

produced in every conceivable variety and

style, but at all prices, to suit the pockets of

almost any class of the community. Blended

with silk thread they are made to look like

a fine lustrous satteen. With figures and

patterns of various kinds thrown up on them

in silk of different hues, they serve as admirable

substitutes for figured silks, both

for ladies’ dresses and waistcoat pieces.

“Backed” with cotton or linen yarn, they

receive a solidity which is very suitable for

many purposes; whilst, with cotton woven

amongst its fibres, the article may be sold at

such a moderate price as at once to bring it

within the reach of the most humble.

There can scarcely be a stronger proof of

the improvements which must have taken

place in this manufacture, than the single

fact—that although, upon its first introduction,

Alpaca wool was but eightpence or

tenpence the pound, and is now worth two

shillings and sixpence, the goods produced

from it are sold at one half the old price.

The principal seat of the Alpaca manufacture,

is at and around Bradford in Yorkshire,

a town which is not only rapidly rising into

importance from the skill and persevering

energy of its manufacturers, but gives every

promise of shortly eclipsing Leeds in general

business.

There can scarcely be a more picturesque

journey than that through the manufacturing

districts of Yorkshire. Approach Bradford

which way you please, you cannot but be

forcibly struck with the beauty of the country

around. Bold hills, gently undulating meadowland,

highly cultivated fields, canals, railroads,

a most charming little river, and all dotted

about with copse and dell, and inoculated

with pretty villas, and lightly sprinkled over

with busy towns—Yorkshire looks like a

somewhat uneven grass-plot stuck about with

bee-hives. It is true the hives are rather

smoky hives; but then the green hills, and

the greener fields, and the fine bracing air,

make one forget the colour of the smoke.

You need not inquire when you are beyond

Lancashire and into the confines of the

West Riding: you can detect the locality

by your nose. There is nothing but wool,

and oil, and water, being knocked about, and

mixed up, and torn asunder, and broken on

savage, unrelenting wheels, and drawn out

into “slivers,” and scalded in hot soap-suds

all day long, and all the year long. It may

rain, hail, thunder, or anything else it pleases,

but it’s all the same to the Yorkshire folk:

there’s no peace for the wool. The whole

county smells fusty, frowsy, and moist: the

length and breadth of the West Riding must

be full of damp great-coats and wretchedly

wet trousers, or I am much mistaken.

Now and then you get a mile or so of fresh

sweet air as you are whisked along in the

train; but only as a short relief from tall,

dark, mysterious-looking buildings, like

county jails or model prisons, with a curling

black stream of smoke above, and another

gurgling black stream of water below, which

would induce one to believe the place to be a

blacking manufactory, and that they were

then busy washing out the old bottles. You

whistle past it, and smell more great-coats

and trousers, and then you come to some more

green fields, rattle over a canal, wind round a

hill, plunge under the high road, whisk round

a corner, and there you are—in the very

heart of damp wearing-apparel—in the town

of Bradford.

If the reader should pay a visit to this

interesting manufacturing town, he will

perhaps feel, as I did, rather surprised to see so

many over-grown school-boys lounging about.

Why, some of those old boys in blue and white

pinafores were really grey-headed. They had

none of their books or slates with them, and,

upon the whole, I thought they were taking

it rather easy. When I entered one of the

large stone factories, I found the ground

floor filled with these elderly lads, and began

to fancy I had walked by mistake into some

extensive national school for adult pupils.

However, this puzzle was soon solved. The

men in pinafores were simply the factory-

labourers, long custom having given them

these long habits, which, however useful, are

far from picturesque.

There is not a very wide difference between

the mode of working up cotton, wool, and

Alpaca, although of course there are many

peculiarities in each set of machines adapted

to the characteristics of the various fibrous

materials. They are all beaten and shaken,

and pulled to pieces, and put together again

and made even and straight, and worked into

“slivers,” and drawn out fine, and then

‘finished,” and finally spun into yarn of

varying thicknesses. In one respect, however,

there is a wide distinction between the working

of cotton, and of wool or Alpaca, the

former never being moistened; whereas both

the latter are not only well washed in hot

soap-suds, but actually put through an oil

bath. Some woollen manufacturers use as

much as three or four hundred tons of olive

oil in one year in the preparation of their

yarns and cloths: very few, even of the

smaller men, but use their tens of tons in that

time.

In the spinning of Alpaca, the process, and

the machinery also, bear a close resemblance

to those of the cotton factories. Except in

some few particulars, a description of one

would be an account of the other. The

alpaca manufacture is, however, chiefly of

interest, from the fact of its supplying us

with fabrics which at once supplant cotton,

silk, and woollen goods, for a multitude of

purposes. Not only have ladies dresses and

children frocks of light summer make, but

the same for autumn and winter. Gentlemen

are provided by means of this fabric

with waistcoating as cool as any cotton, yet

rich and lustrous as the best silk patterns.

Dwellers in tropical countries are thankful to

possess a black coat, which, while it represents

a cloth coat, is not a fourth of the

weight, nor a half of the price. Boots, caps,

parasols, bonnets, trousers, cloaks, and I know

not how many other things equally useful,

may now be composed entirely or partly of

this material.

There is, however, one building of Cyclopean

proportions, rearing its Titan head—or, just

at present, not more than its trunk—above

the green fields of the Bradford neighbourhood,

which deserves a passing notice, inasmuch

as there is not only nothing equal to it in

all Yorkshire or Lancashire—and that is

saying something; but, when finished, there

will doubtless be no factory in the world that

shall approach it in magnificence, in extent, or

in completeness of purpose.

This one factory, which is to be the astonishment

of the manufacturing world, is in course

of erection by the same person who, sixteen

years since, caused so much amazement in

the establishment of C. W. and F. Foozle and

Co. about those three hundred and odd dirty

bales of South American stuff. Mr. Titus

Salt, of Bradford, is engaged in constructing a

factory capacious enough to contain within

its walls the machinery, or, rather, the

equivalent to the machinery, now working in five

of his Alpaca mills scattered over various

parts of the vicinity.

At a distance of two or three miles from

Bradford, the traveller by the Leeds Railway

may observe a sweet spot of country where the

river Aire meanders gently through as pretty a

green valley as is to be seen for many a league.

On that spot, just where the Lancaster and

Glasgow Railway and the Leeds and Liverpool

Canal diverge from each other, is a

block of ground, now fast disappearing

beneath a vast pile of masonry. This is the

Saltaire estate, and is destined to receive

the whole of Mr. Salt’s operations, with new

machinery and engines more than equal to

his present force. The mill or factory is so

situated with regard to the railway and

the canal, that goods may be conveyed to it

by either of them without the aid of cartage

or porterage.

This vast building stands upon six acres of

ground, running east and west, and is nearly

six hundred feet in length, and eighty in

height: the several floors and sheds will

comprise a superficial extent of nearly fifty-

six thousand feet.

Such is, and such will be, Saltaire; and

the whole of this, it must be borne in mind,

is created by the genius and industry of one

quiet man of business. All these vast

machines, these huge piles of works, these

myriads of working instruments, this wonderful

whole, spring from that one source—

those three hundred and odd dirty bales of

frowsy South American stuff.